Senas: Preserving a Medieval Game from Lorca

I'm thrilled to share that my project to digitize the medieval game of senas has been featured in La Placeta de Lorca, a local cultural publication. You can play it right now at lassenas.es. Building this taught me a lot about game architecture, finding the right abstractions, and developing heuristics.

What is Senas?

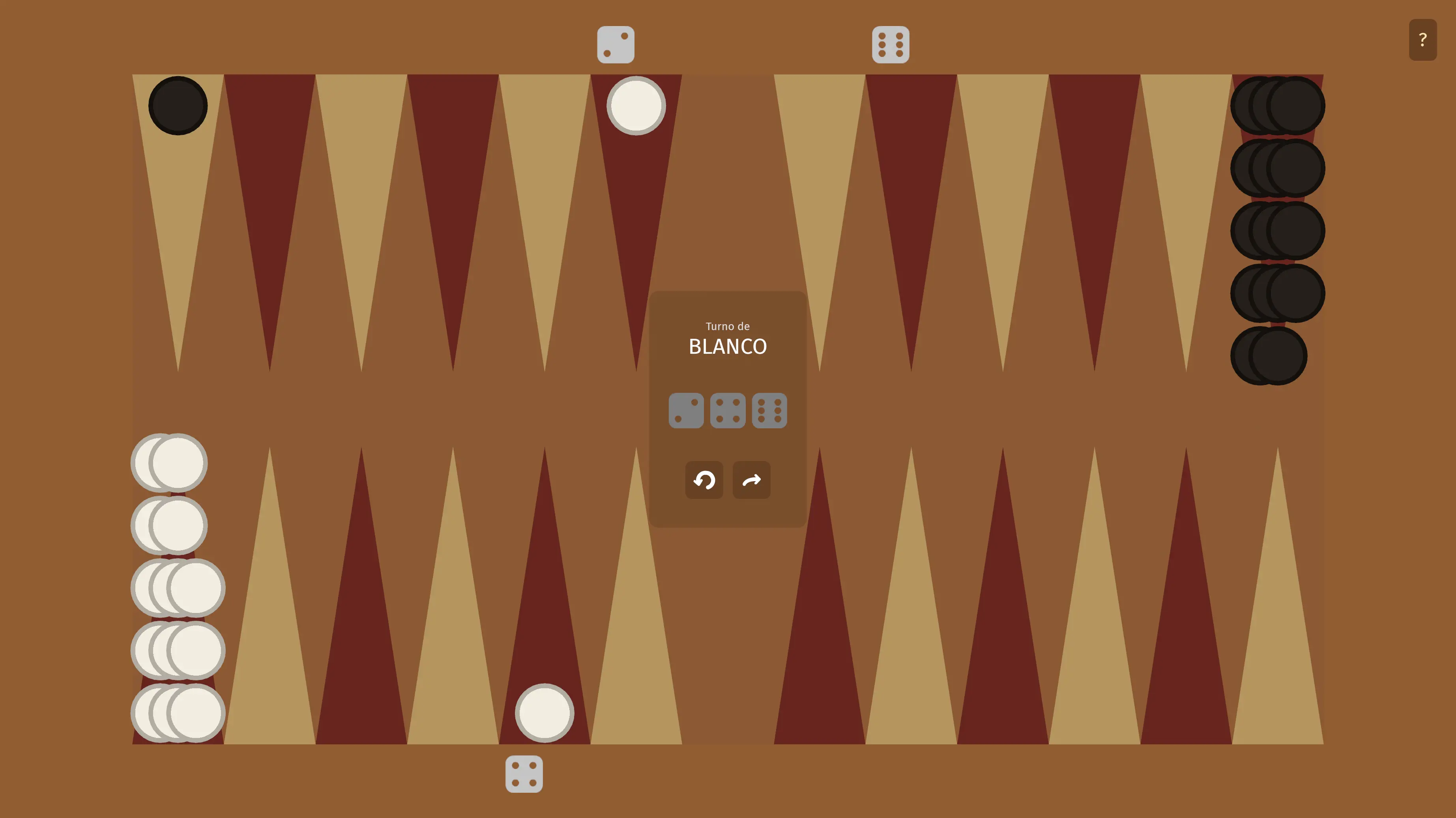

Senas is a medieval board game from Lorca, Spain, a race game similar to backgammon where two players move their pieces around a circuit trying to reach the goal before their opponent.

The Board: Four "senas" (sections), each with six holes, 24 positions total. Each player has 15 pieces that all start grouped in the first hole. The goal is to move all pieces through the complete circuit before your opponent.

How to Play:

Starting: The first piece must circle the circuit alone and reach the fourth sena before any other piece can enter. Once it's in the fourth sena, subsequent pieces can enter the circuit while avoiding having three occupied positions in the first sena at the end of the turn.

Rolling and Moving: Players roll three dice. All three dice values must be executed separately—you can't sum them. Each die value represents one independent move. If two or three dice show the same number, they count double (four or six of that value).

Blocking: You can't land on a hole occupied by an opponent's piece, but you can occupy holes with your own pieces. You can pass over an opponent's piece if you don't stop there.

The "Tute": Rolling triple sixes is a "tute." You count double scores (six moves of six points) and get to roll again.

Unused Dice: If you can't use all your dice points because of piece positioning, your opponent gets to use those unused points before their own roll.

Bearing Off: You can only start exiting the circuit when all your pieces are grouped in the fourth sena. Excess points can be used as exact scores at the end.

The Story

Senas is a medieval board game from Lorca, Spain. It's a game that I used to play with my grandfather, so I have a personal connection to it.

Architecture: A Three-Crate Rust Workspace

I split the project into three crates for clear separation:

senas - The core game representation and engine

- Board representation and state management

- Move generation and validation (~2600 lines of code)

- Roll mechanics and special rules

senas_players - AI strategies

- Pluggable player trait for different decision-making algorithms

- Random player, easy difficulty

- Heuristic player, tries to balance some heuristics such as occupying more space

- Expectiminimax player, applies the heuristic for possible future states

- Tournament and profiling tools for evaluating AI strength

senas_bevy - The interactive UI

- Bevy game engine for rendering and input handling

- WebAssembly compilation for web deployment

This made it easy to develop and test game logic separately, profile different AI players, and run them against each other.

Translating Rules to Code

Putting senas into code required formalizing rules that are easy in person but a bit tricky to model:

You must use all three dice values separately. The tricky part is preventing illegal board states—like ending your turn with more than three pieces in the starting position. I had to validate move sequences, detect invalid states, and allow undoing moves if someone miscalculated.

The AI: Phase-Adaptive Heuristics with Pruning

For the game tree search the main challenge was managing the search space efficiently.

With three dice values to distribute among multiple pieces, you get way too many possible move sequences. But a lot of them reach the same board state. For example, moving piece A by 3 then piece B by 5 produces the same result as moving piece B by 5 then piece A by 3. Rather than evaluate both, I prune duplicate final states during move generation, keeping only the strategically distinct outcomes.

With that optimization, the heuristic scoring looks like:

Detect the current game phase based on piece positions

Apply different weights to evaluation metrics depending on phase:

- Opening: Prioritize getting your first piece advancing

- Development: Spread pieces efficiently to reduce blocking risk

- Racing: Move all pieces toward the goal quickly

- Bearing Off: Exit pieces optimally

Select the move that leads to the biggest score (or explore the search tree for the expectiminimax player)

The Core Architecture: Player Trait and Async Channels

I knew I wanted different player types (AI, human, etc.) to coexist in the same game loop. This would make it easier for testing and developing new AI strategies. The cleanest way I found was a pluggable player system using async traits and channels.

The Player Trait

At the heart of the design is a simple trait that abstracts "anything that plays senas":

The game loop doesn't care who is playing, as long as it implements the trait.

Multiple Player Implementations

Because of this abstraction, adding new player types is straightforward:

- HeuristicPlayer: Phase-aware strategy with tunable evaluation weights. Used in VsAi mode.

- RandomPlayer: Baseline for testing. Picks moves uniformly at random.

- ExpectiminimaxPlayer: Game tree search with dice roll uncertainty. Slower but stronger.

- HumanPlayer: Accepts moves from user input.

- BevyPlayer: Sends bevy events when receiving messages to update the Bevy game state and adapts the human input.

You can mix and match: VsAi uses HeuristicPlayer, VsHuman uses two HumanPlayer instances, or tournament mode can pit HeuristicPlayer vs ExpectiminimaxPlayer.

Switching player implementations at startup means swapping one struct for another. No refactoring the entire game loop.

Future Possibility: The async channel architecture makes networked multiplayer feasible. Instead of a channel to a local Bevy system, you'd have one to a remote player's computer. The game loop would work the same way—it's still just awaiting moves on a channel.

The Bevy Adapter

The tricky part is integrating async Rust game logic with Bevy's synchronous frame-based update loop. The solution is an adapter that bridges them with channels:

The BevyPlayer struct implements the Player trait and uses tokio's mpsc channels:

- Sends game events to Bevy (dice rolls, opponent moves, etc.)

- Receives player decisions from Bevy (validated moves chosen by human or AI)

- Watches a shutdown signal so the game can cleanly exit

When the core game asks a player to make moves, the BevyPlayer:

- Sends a

MakeMovesmessage down a channel to Bevy - Awaits a response on another channel (provided by the UI)

- Returns the validated moves to the game loop

Meanwhile, on the Bevy side, different systems handle different players:

- For AI: A system reads the

MakeMovesmessage and immediately sends back a decision from the AI algorithm - For humans: UI systems handle dice rolls, movement selection, and validation before sending the decision

The UI

I started with Bevy's UI system but switched to 3D mesh rendering to get animations and shader effects. The board is 24 triangles with pulsing highlights, and pieces animate smoothly between positions.

WebAssembly and Deployment

To get the game online, I compiled it to WebAssembly and deployed on Cloudflare Pages. The WASM file ended up larger than Pages' asset limit, so I store it in Cloudflare R2 and serve it from Pages. I set up a GitHub Actions workflow that compiles the project, runs tests, and deploys automatically. I used the usual WASM optimizations—aggressive size reduction, panic-as-abort, embedded assets. Everything runs client-side and is free to host.

Next Steps

The game is live at lassenas.es. Some things I might work on:

Self-play AI: I've experimented with training an AI through self-play, which would be stronger than the heuristic player. Getting a neural network to run in WebAssembly is tricky though—I've looked at ONNX but it's not straightforward. It's a possible future direction.

Online multiplayer: The player trait architecture would make this feasible—people could play from separate machines.